One morning, in a small apartment in Bombay, a girl of about sixteen looked up from the newspaper and said excitedly, ‘Pandit Ravi Shankar’s playing tomorrow at the Shanmukhananda Auditorium.’ ‘Sh-sh,’ said her mother pointing to the figure sleeping on the bed. ‘You’ll wake him up. You know he needs all the sleep and rest he can get.’

But the boy on the bed was not asleep. ‘Pandit Ravi Shankar!’ he

said. ‘Pandit Ravi Shankar, the sitar maestro?’ He raised himself up on

his elbows for one second, then fell back. But his eyes were shining. ‘We

mustn’t miss the chance,’ he said. ‘I’ve –I’ve –always wanted to hear him

and see him…..’

‘Lie down son, lie down.’ His mother sprang to his side. ‘He actually

raised himself up without help,’ she murmured with a catch in her throat

and her eyes turned to the idols on a corner shelf. The prayer which she

uttered endlessly came unbidden to her lips.

‘I must hear him and see him,’ the boy repeated. ‘It’s the chance of

a lifetime.’ Then he began to cough and gasp for breath and had to be

given oxygen from the cylinder that stood under the bed. But his large

eyes were fixed on his sister.

Smita bit her lip in self-reproach. She had been so excited at seeing

the announcement that she had not remembered that her brother was

very ill. She had seen how the doctors had shaken their heads gravely

and spoken words that neither she nor her parents could understand.

But somewhere deep inside, Smita had known the frightening truth that

Anant was going to die.

The word cancer had hung in the air- her brother

was dying of cancer even though she pretended that all would be well

and they would return together, a small family of four, to their home

in Gangapur. And he was only fifteen, and the best table-tennis player

in the school and the fastest runner. He was learning to play the sitar;

they were both taking sitar lessons, but Anant was better than her as in

many other things. He was already able to compose his own tunes to the

astonishment of their guru. Then cancer had struck and they had come

to Bombay, so that he could be treated at the cancer hospital in the city.

Whenever they came to Bombay the family stayed with Aunt Sushila.

Her apartment was not big but there was always room for them.

They had come with high hopes in the miracles of modern science. They

told themselves that Anant would be cured at the hospital, and he would

again walk and run and even take part in the forthcoming table-tennis

tournament. And, he would play the sitar and perhaps would be a great

sitarist one day. But his condition grew worse with each passing day and

the doctors at the cancer hospital said, ‘Take him home. Give him the

things he likes, indulge him,’ and they knew then that the boy had not

many days to live. But they did not voice their fears.

They laughed and

smiled and talked and surrounded Anant with whatever made him happy.

They fulfilled his every need and gave whatever he asked for. And now he

was asking to go to the concert. ‘The chance of a lifetime,’ he was saying.

‘When you are better,’ his mother said. ‘This is not the last time they are

going to play’.

Smita stood at the window looking at the traffic, her eyes filled with

tears. Her mother whispered, ‘But you Smita, you must go. Your father

will take you. ’When she was alone with Aunt Sushil, Smita cried out in a choked voice, ‘No, how can I? We’ve always done things together, Anant and I.’ ‘A walk in the park might make you feel better,’ said Aunt Sushil and Smita was grateful for her suggestion.

In the park, people were walking, running; playing ball, doing yogic

exercises, feeding the ducks and eating roasted gram and peanuts. Smita

felt alone in their midst. She was lost in her thoughts.

Suddenly a daring thought came to her and as she hurried home she

said to herself, ‘Why not? There’s no harm in trying it.’

‘It would be nice to go to the concert. I don’t know when we’ll get

another opportunity to hear Pandit Ravi Shankar,’ she said to her mother

later. And her father agreed to get the tickets.

The next day as Smita and her father were leaving for the concert, her brother smiled and said, ‘Enjoy yourself,’ though the words came out in painful gasps. ‘Lucky you!’

Sitting beside her father in the gallery, Smita heard as in a dream the thundering welcome the audience gave the great master. Then the first notes came over the air, and Smita felt as if the gates of enchantment and wonder were opening.

Spellbound, she listened to the unfolding ragas, the slow plaintive notes, the fast twinkling ones, but all the while the plan she had decided on the evening before remained firmly in her mind. ‘The chance of a life time’. she heard Anant’s voice in every beat of the tabla. The concert came to an end and the audience gave the artists a standing ovation. A large mustachioed man made a long boring speech. Then followed the presentation of bouquets. Then more applause and the curtain came down. The people began to move towards the exits.

Now was the time. Smita wriggled her way through the crowds towards the stage. Then she went up the steps that led to the wings, her heart beating loudly. In the wings a small crowd had gathered to talk about the evening concert, to help carry bouquets and teacups and instruments.

He was there, standing with the man who played the tabla for him the great wizard of music, Ustad Allah Rakha. Her knees felt weak, her tongue dry. But she went up, and standing before them, her hands folded, ‘Oh Sir,’ she burst out. ‘Yes?’ he asked questioningly but kindly. And her story came pouring out, the story of her brother who lay sick at home, and of how he longed to hear him and the Ustad play. ‘Little girl,’ said the mustachioed man who had made the long speech. ‘Panditji is a busy man. You must not bother him with such requests.’ But Pandit Ravi Shankar smiled and motioned him to be quiet. He turned to Ustad Sahib and said, ‘What shall we do, Ustad Sahib?’ The Ustad moved the wad of paan from one cheek to another. ‘Tomorrow morning we perform for the boy-Yes?’ he said. ‘Yes’, Panditji replied. ‘It’s settled then.’

It was a very excited Smita who came home late that night. Anant was awake, breathing the oxygen from the cylinder. ‘Did you-did you hear him?’ he whispered. ‘I did,’ she replied, ‘and I spoke to him, and he’ll come tomorrow morning with the tabla Ustad, and they’ll play for you.’

And the following morning, Aunt Sushil's neighbors saw two men getting out of a taxi which pulled up outside their block…They could not believe their eyes. ‘It is…It’s not possible?’ they said.

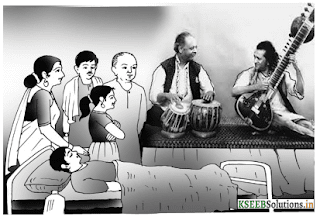

Pandit Ravi Shankar and Ustad Allah Rakha went up the wooden staircase and knocked softly on the door of Aunt Sushil's apartment. They went in, sat down on the divan by the window and played for the boy, surrounding him with a great and beautiful happiness as life went out of him, gently, very gently.

{This is a true story, but all the names except Pandit Ravi Shankar's and Ustad Allah Rakha's have been changed.}

0 Comments

Post a Comment